Exposing the Power Grid: Exercises in Energy Literacy

This dispatch is a proposal to complicate two classic exercises in how to foster energy literacy: one from environmental design and the other from the energy humanities.

It’s October 2022; I am walking along the Teltow canal in Berlin with a group of geography and design scholars and we are doing fieldwork. Our objective is to observe the ways in which the power grid shapes our everyday lives and constrains our ability to imagine and design for anti-catastrophic energy futures.

Lichterfelde Power Plant

©James Auger 2023

The Teltow Canal is emblematic of the tensions among the multilayered configurations of the power grid—material, political, social, and cultural—that already exemplify what I mean by “complicate”. It passes the Lichterfelde power plant, which looms behind the trees and seems weirdly out of place. Before the wall came down the plant was located in East Germany and ran on heavy oil; it later switched to natural gas and eventually shut down in the course of the German 2030 Climate Action Program. Running alongside and extending the death strip of the wall for a section of more than four kilometers, the canal itself is an infrastructure of power in multiple ways: As an important link between rivers and rapidly industrializing cities it allowed for the distribution of raw materials and industrial goods during the Prussian Empire. As a channel for barges that transported coal in the 1920s it was crucial for AEG and Siemens, both energy companies with headquarters in Berlin and key players in the development of the electrical grid in Europe and North America. In the same way that the canal built linkages, it also withheld contact and interrupted flows of people, resources, and ideologies between East and West. We pass a plaque commemorating Roland Hoff who was shot in 1961 trying to swim across clinging to his briefcase. We encounter ascending steps in various states of ruin, haunting remnants of a former footbridge that hint at a connection discontinued. Today the Teltow canal is part of a renovated canal system across Germany and still transports raw materials across the continent through Berlin waterways, removing waste and bringing biomass to the new power plants in the city. In other words, the mutual inflections of the Teltow Canal and the power grid are complex and hardly containable.

EXERCISE ONE: Catching Energy

The first stage of our fieldwork is to identify energy transformations happening in our immediate surroundings and to sense and analyze the local energy landscape of Berlin with regard to flows and dissipation. I look around: The thick rubber boots I am wearing not only insulate my feet from the cold but also dampen the sensation of my soles meeting the wet ground covered with autumn leaves that are starting to compost and exude the sweet odor characteristic of this time of year. Down by the water commercial fishermen are dipping their poles into the opaque water. Transparent plastic boxes filled with maggots that quiver like static on a television screen pile up by the side of the footpath. It is apparent that energy is everywhere. We hear it in the noise of gushing water, in the murmur of the wind, and the sound of wheels on asphalt. We see it in the red glow of a passerby’s cheeks. We smell it in car exhaust and smoke from grilled sandwiches at the market. Our bodies vibrate in resonance with footsteps, guitar strumming, screams and chatter, construction sites and rushing traffic. We feel it as the rays of the sun bounce off windshields and hit our skin.

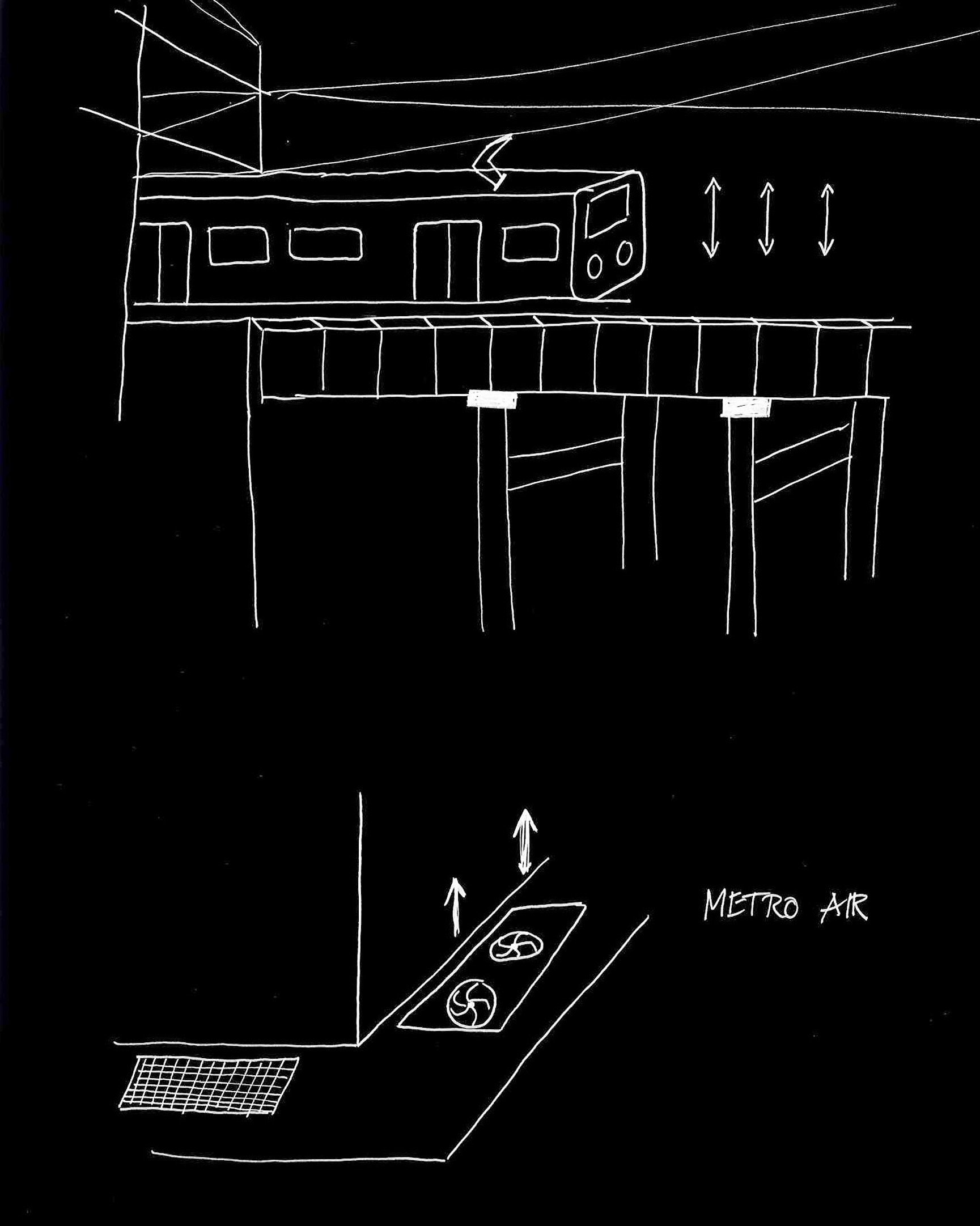

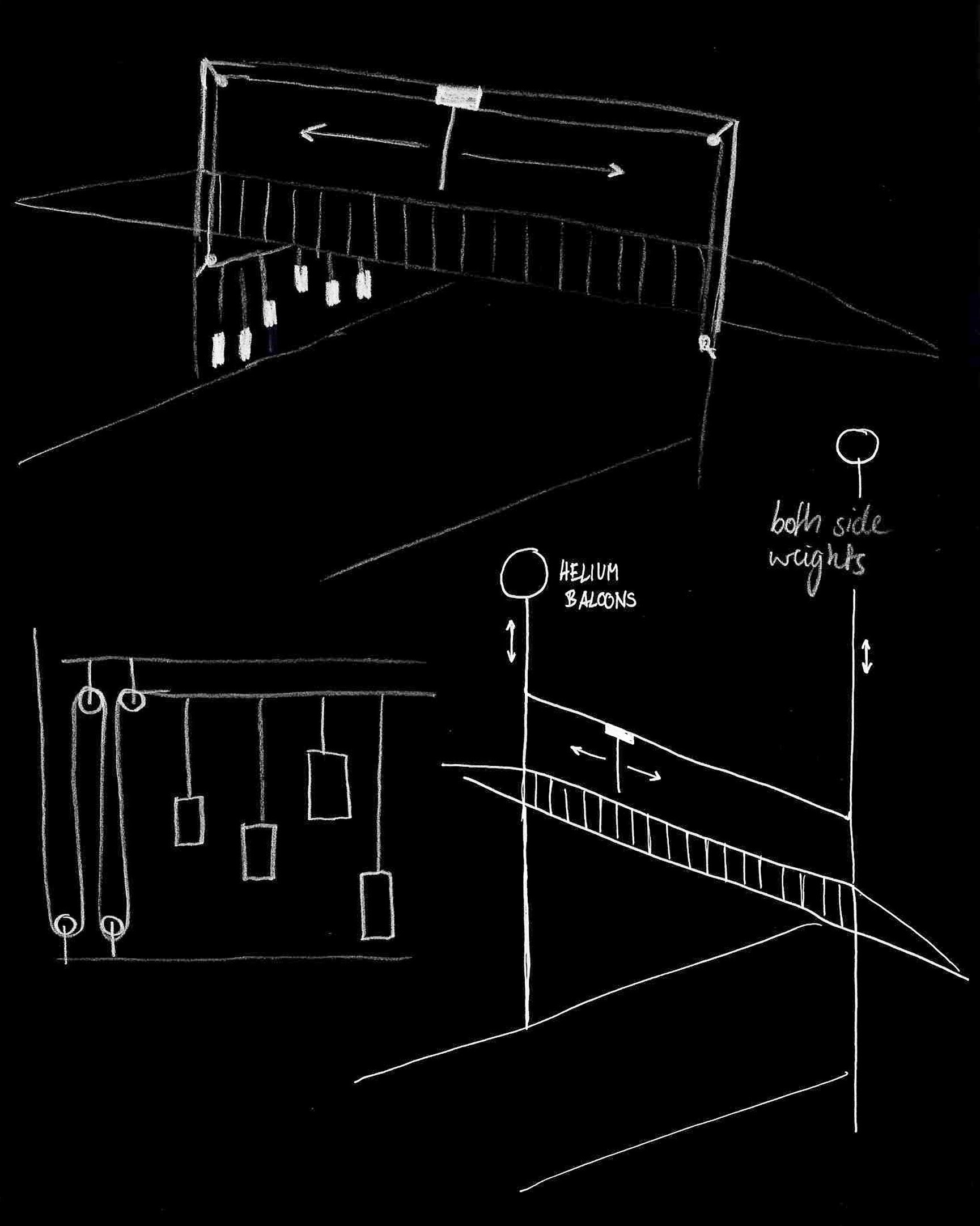

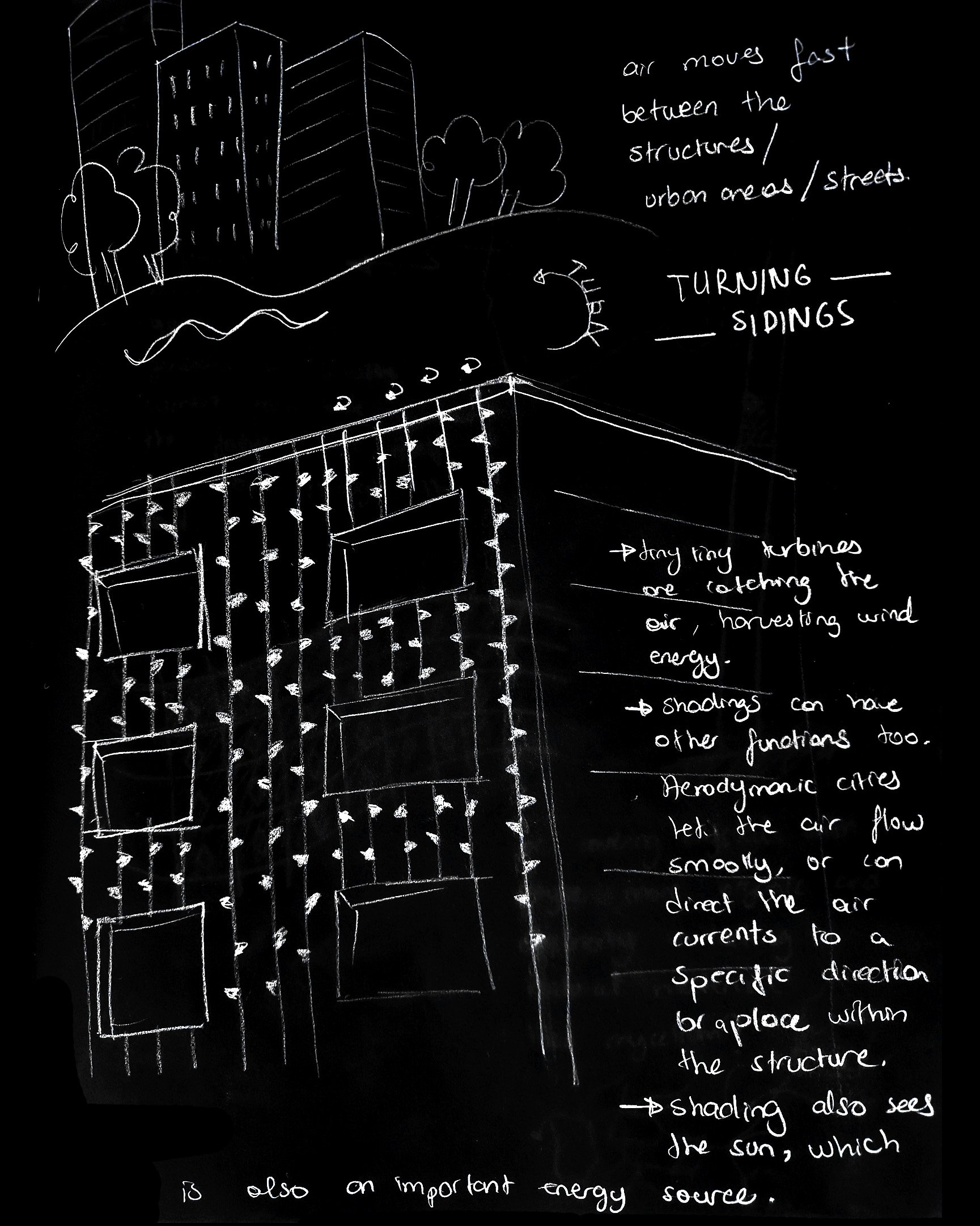

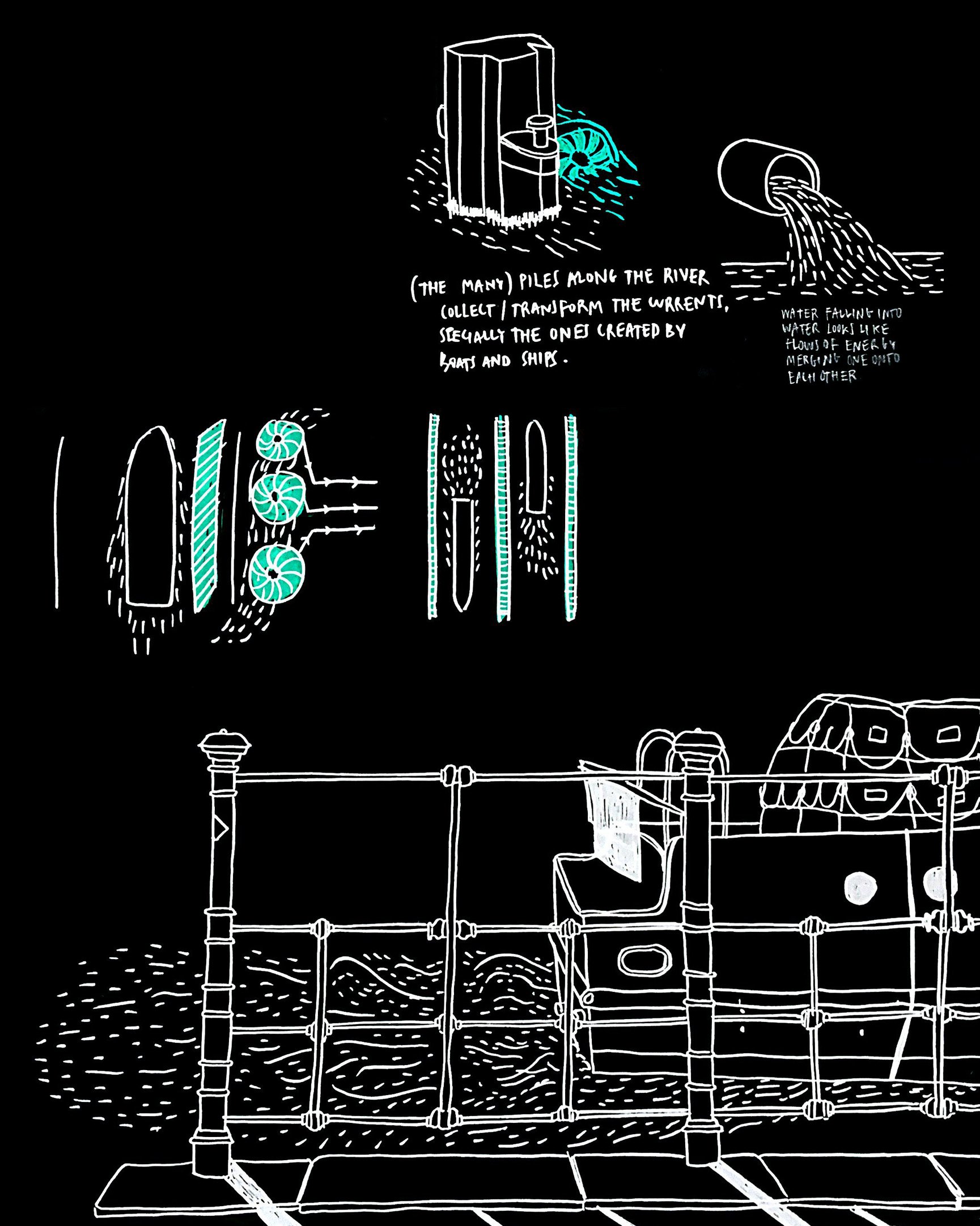

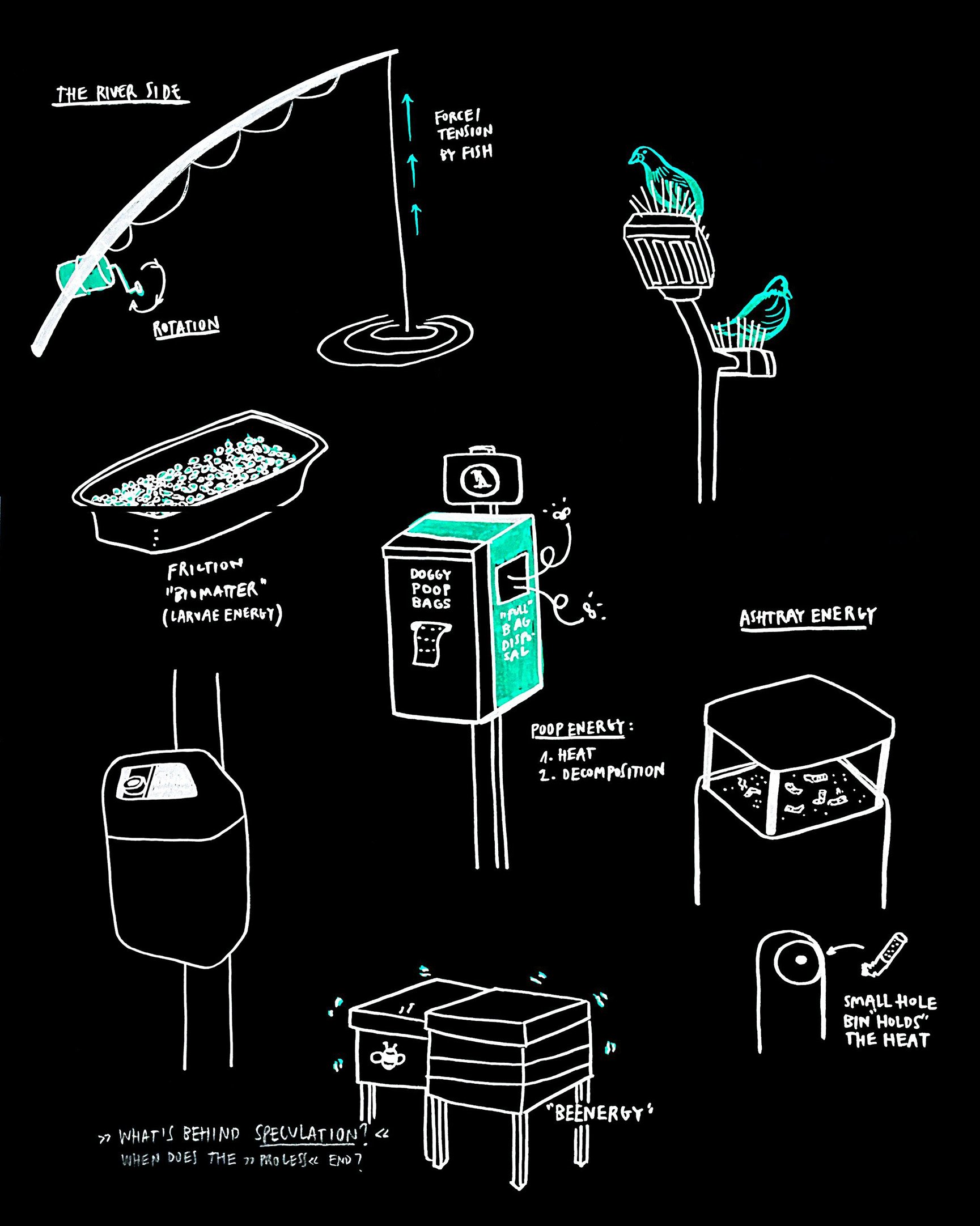

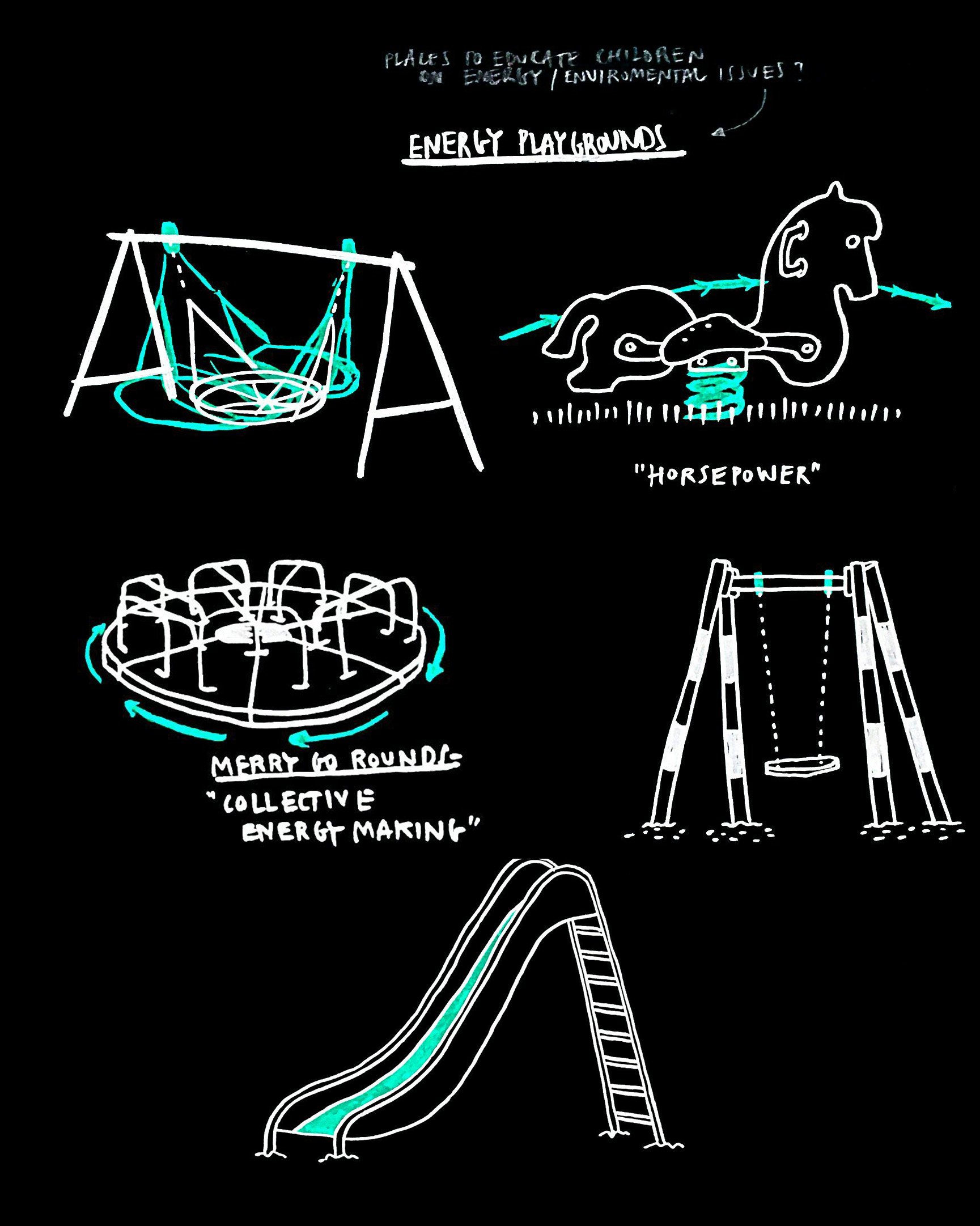

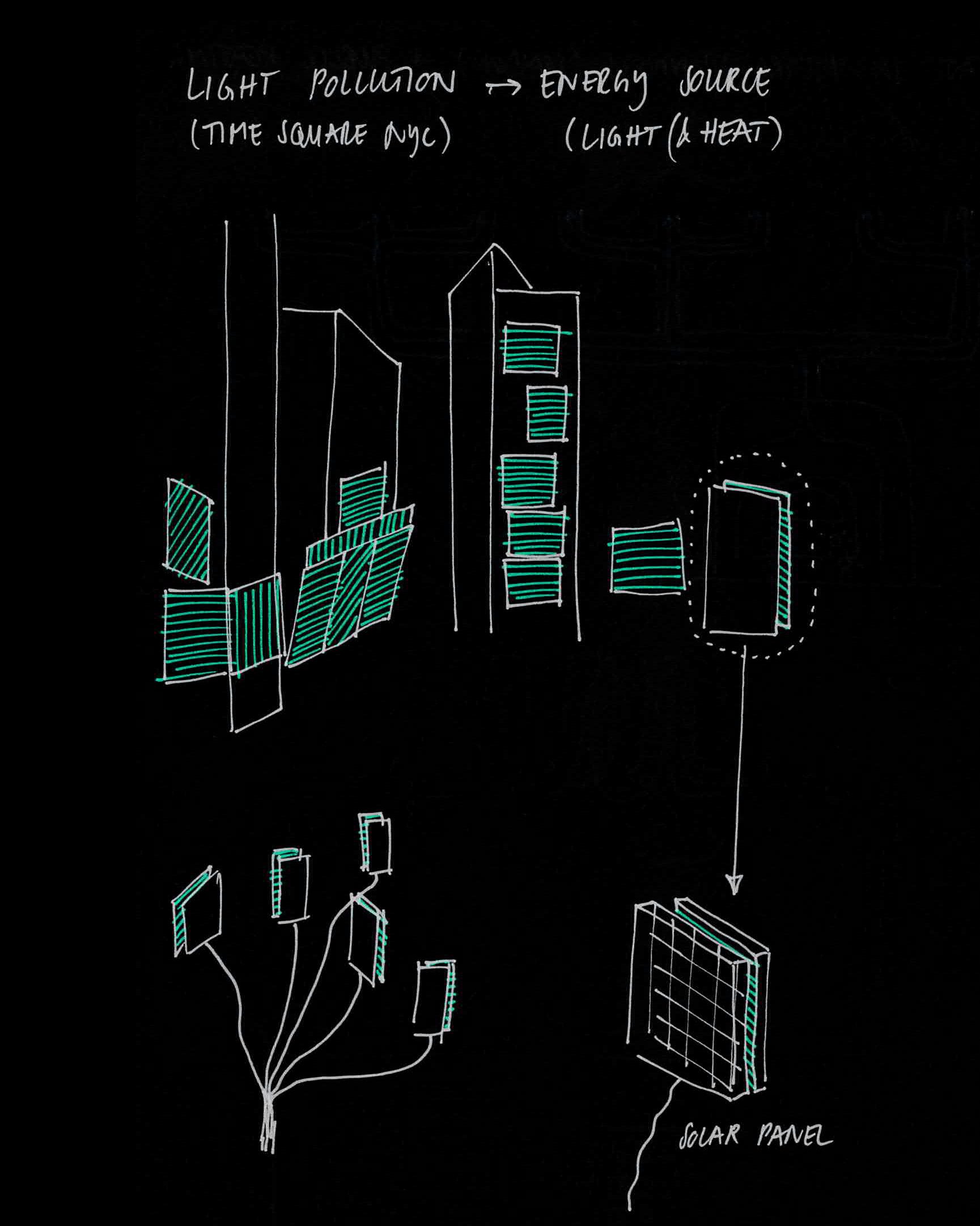

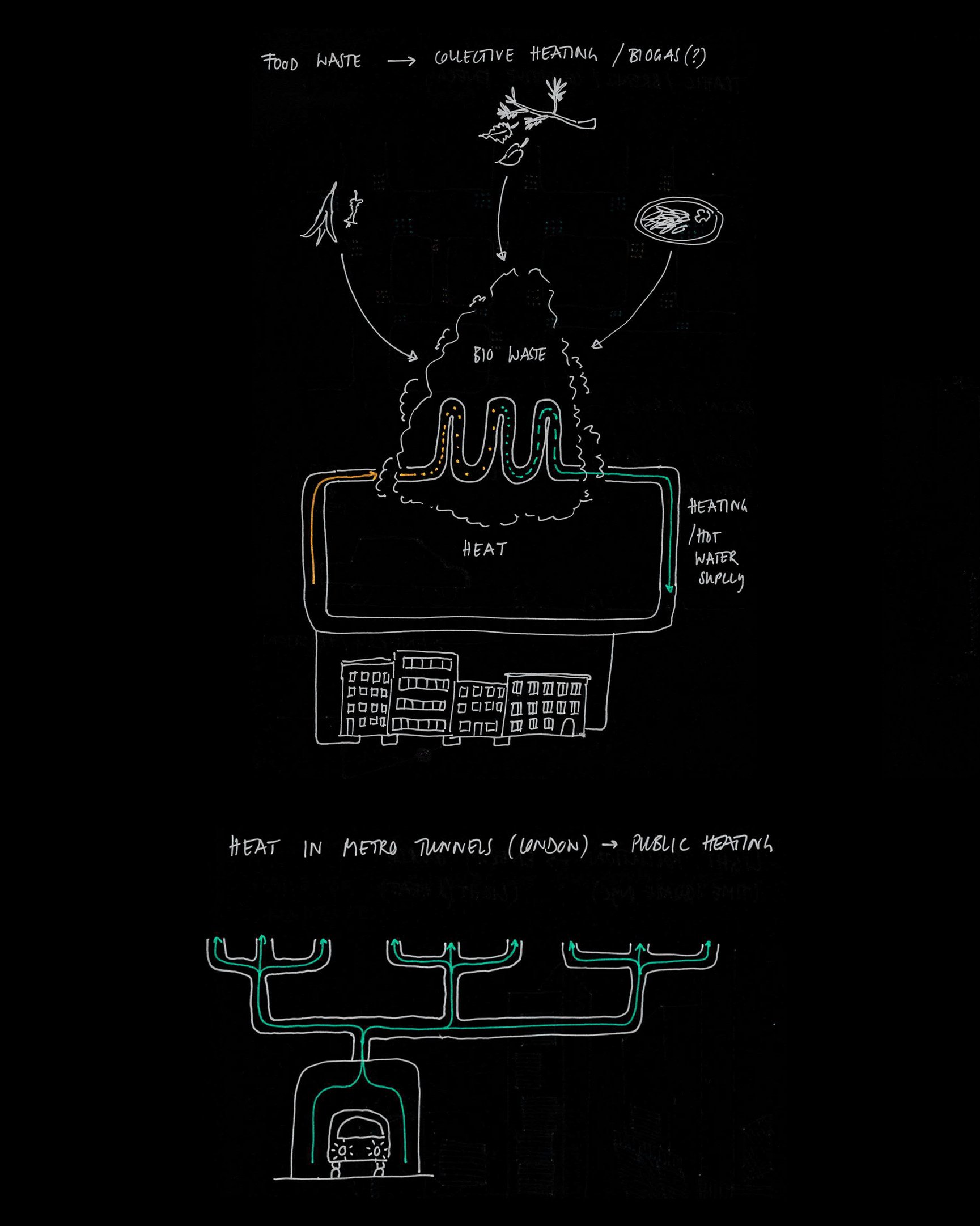

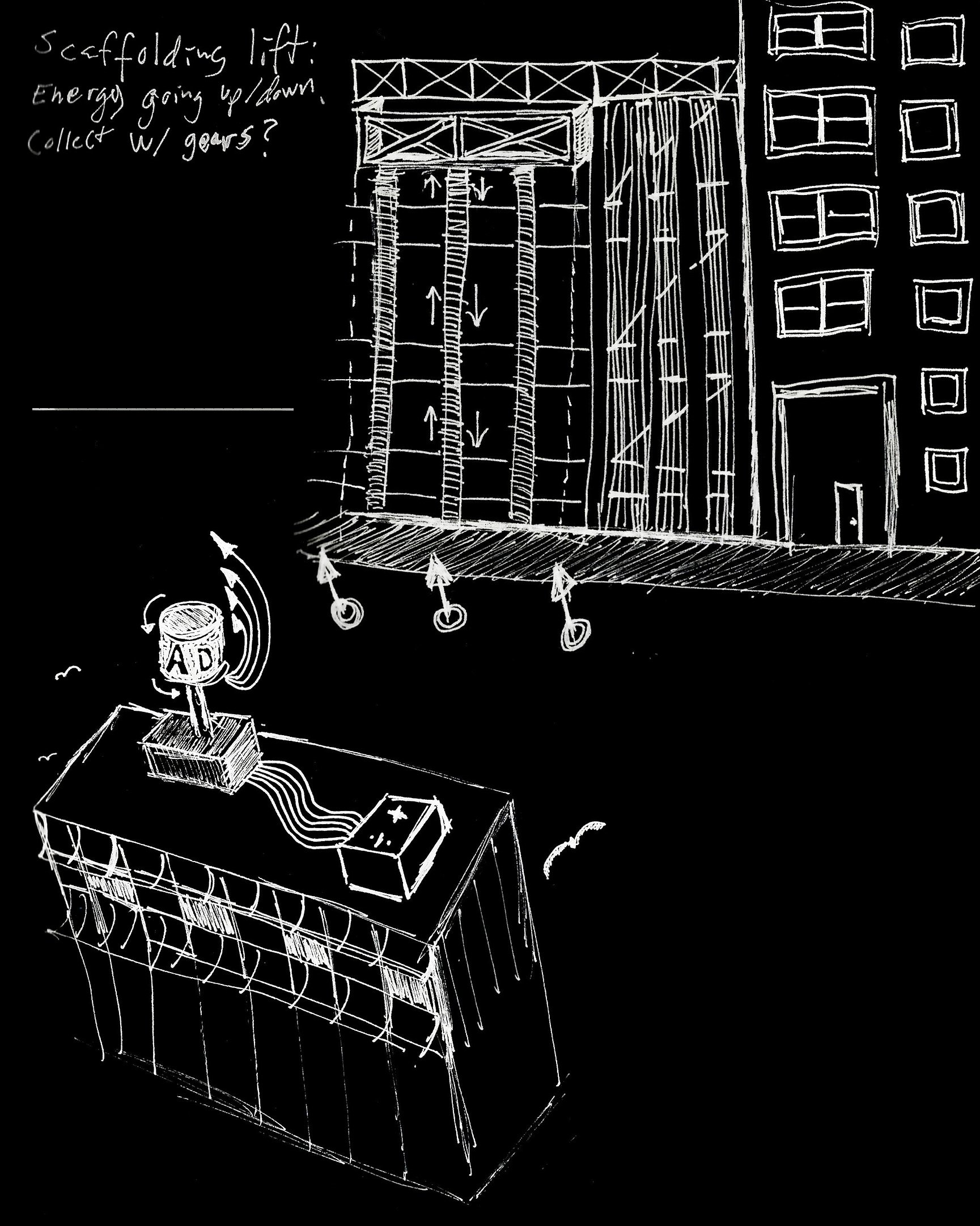

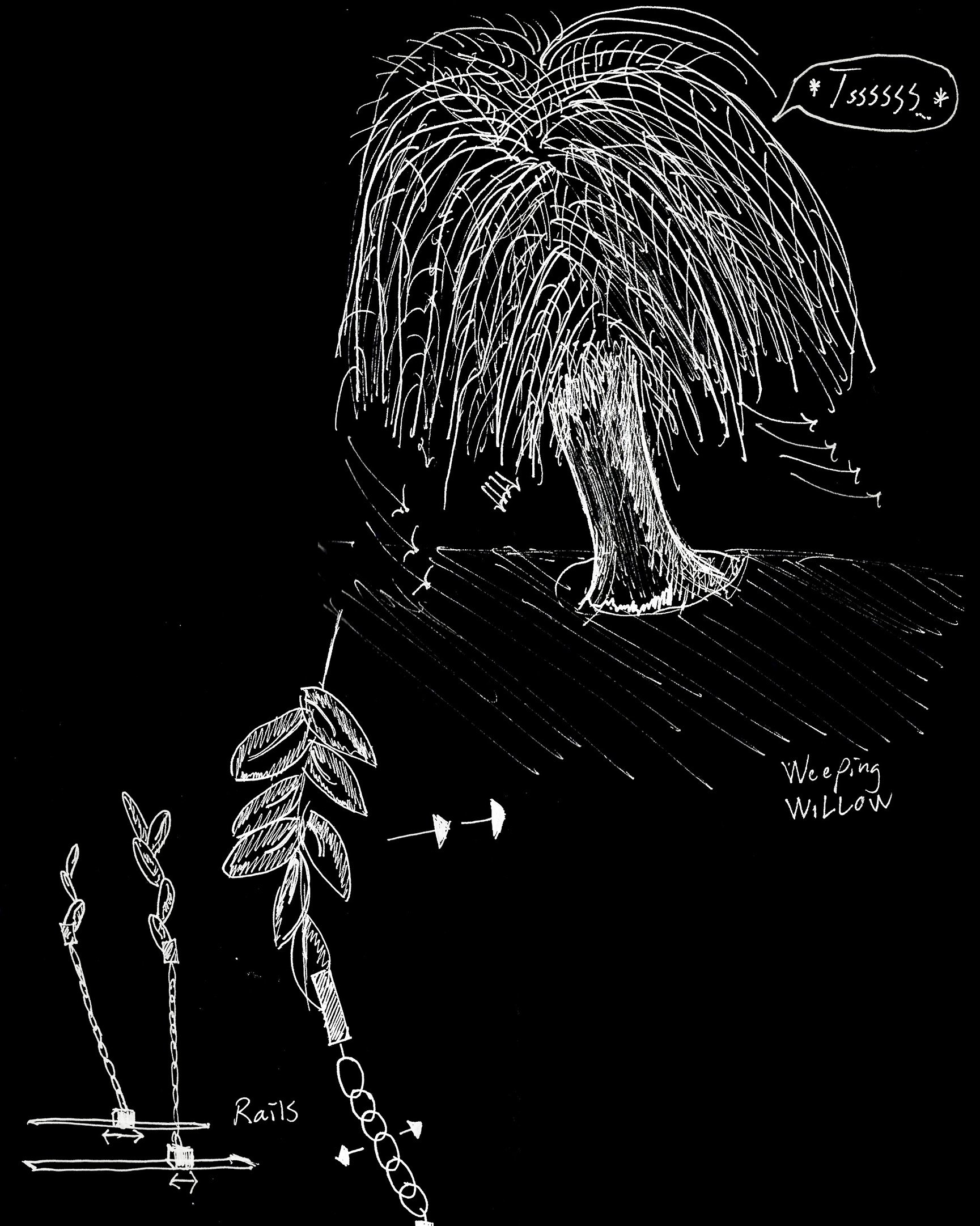

The classic design exercise is solution-oriented: How might we collect this energy and transform it so it is not lost in the atmosphere? What are the specific local conditions and possible chances for design to intervene? Quickly our sketchbooks fill with speculations on how to hack our immediate surroundings. By strategically placing turbines where hot air from subway tunnels escapes through air ducts, or using weight mechanisms to collect potential energy from the kinetics of people moving through public space we imagine ourselves as harvesters of heat, wind, and water energy who try to think beyond the electrical grid of the city.

Collected sketches from our group, including work by Mads Bering, Ottonie von Roeder, Jordi Tost, Rupert Neuhöfer, Ilkin Tasdelen

But this is where it gets complicated: Even if we were able to catch, store, and transform urban energy through our made-up collectors hidden under merry-go-rounds, and our solar panels could siphon energy from Berlin’s light-polluted night sky, our sketches compel us to ask a follow-up question: Once we caught energy–what are we using it for? If power grids shape the realities of our lives, daily routines, traditions, and values–what kind of lives did our interventions stipulate?

Envisioning alternative energy futures by catching dissipated power in the urban landscape does not automatically come with a change of urban life. Even though we are hacking the energy grid, we are not hacking the patterns of distribution, consumption, exhaustion, and extraction that sustain it. Our design provocations are situated within the cultural geography of Berlin and as such also within the belief systems that shape the ideas of what we want to use energy for. By hacking the infrastructure without questioning if the interactions it conditions remain the same, we envision different energy futures but affirm contested energy politics. To put it this way: Even if the treadmill was able to store the energy we give off, would we still drive our car to the gym and idealize the same body types?

EXERCISE TWO: Visiting the grid

To better understand how energy infrastructures inform the urban environment and the way we act in it, with it, and beyond it, the second stage of our fieldwork encourages encounters with the physical constituents and locations of the electrical grid, and I am reminded of what Shannon Mattern calls “infrastructural tourism”.

The walk along the canal, crossing bridges, streets, and abandoned train tracks eventually leads us to the Berlin Energy Museum. A building that was once the world’s largest battery storage facility now exhibits turbine blades, discarded machinery to process coal, household appliances from throughout the 20th century, and paper models of the evolution of power plants—the histories and hidden materials of the „electropolis“ Berlin. It was founded in 2001 by a private association of 150 energy enthusiasts, including four women, as our tour guide—a retired physics teacher—is amused to share.

Retracting levers, crusty conveyor belts, and pneumatic pumps click, rumble, growl, screech, and bang incessantly. Noise is a sign of energy transformation and dissipation. Entropy in progress. We can hear it all the time, especially loud here in the museum.

More than once we are plugging our ears as we huddle in a semicircle around our tour guide. In one hallway we encounter “Herby”, a slightly battered mannequin dressed in a boiler suit, helmet, gloves, and boots, fixing a leak in the electrical grid—a busted pipe or severed cable perhaps. Our objective is to become sensitive to encounters with infrastructures that usually remain unseen: the material worlds behind the socket; the greater systems of designed objects.

But this is where it gets complicated: Making energy infrastructures visible is not a matter of simply prying open the ground and ripping out electrical cords to see what is underneath. It also entails an engagement with the stories that unfold if we consider for example the raw materials they are made of, or the kinds of interactions they allow, account for, or amplify. Visiting the electrical power grid requires seeing not only what’s located under the asphalt, behind a wall, on the outskirts of town, or under water, but also analyzing the local and global conditions these infrastructures point to. The museum is full of such multilayered encounters with material actors of the grid that tell stories of power.

In one of the rooms on the second floor, placed on a washing machine from the 1920s is a framed advert from Siemens, one of Germany’s industrial giants at the time, producer of electrical household appliances and radios in large quantities via the assembly line. The ad from 1928 shows a young, slender, white woman holding the plug of a washing machine. Her posture and a coat thrown over her arm indicate that she is about to leave. Her chic dress and finger-waved hair let us assume that it is to some place fancy. A party maybe. The headline „Inzwischen wäscht der Protos“ („Meanwhile Protos does the laundry“) tells us that women are temporarily relieved from their chores by an electrical machine. It tells us that they are empowered by plugging in. This poster is an example for the ways in which power shapes the lives of those who receive it and how gender politics are embedded in energy politics.

Advertising poster from 1928 showing an elegantly dressed white women plugging in a washing machine.

©Johanna Mehl 2023

But 1920s Berlin households not only received electricity through the power line, they were also interpellated through the power line. Aside from washing machines, Siemens produced the “Volksempfänger”, a radio receiver with the sole purpose of transmitting national socialist propaganda. We find one in a different room on the same floor as part of a radio collection. It still had a note attached to it, warning that the listening of non-nationalist radio stations was considered a criminal offense. In a quite literal way, the “Volksempfänger” is an example of how energy infrastructures amplify political power.

On another floor we encounter hundreds of cross-sections of cable ends that are lined up like trophies on shelves. Layers and layers of rubber, copper, and aluminum. This is what the grid is literally made of–materials whose genealogy in the Global South makes apparent the entanglements between the power grid and colonial exploitation. These cross-sections not only expose the raw materials that conduct and insulate electrical power, they are also a representation of imperial hegemonies and environmental racism. What’s more, the way that these technologies of power are displayed is an example for the ways in which politics are not only deeply embedded into the material components of the electrical grid, but also in the very idea of it. In that same room, displayed on a table in the corner, I notice a laminated photograph of a narrow street in a South Asian village. It foregrounds a huddle of electrical cords that connect run-down buildings next to and across from each other. The caption includes a racist joke that builds on the contrast between what we are supposed to read as premodern and the well-hidden, accurately arranged, and allegedly sophisticated way of distributing electricity in Berlin. As the ultimate rational structure connected to ideas of conquest, technological progress, management, and “civilization”, the power grid symbolizes an order of the mind that demarcates messy things as lesser things. A visual order is taken as grounds to declare technological superiority and serves as an example for how the power grid conducts as well as embodies, symbolizes, and conditions power relations.

Black and white, high contrasted photograph of a shelf that displays various sizes of cable ends.

©Ilkin Tasdelen 2023

Thinking with complications

Both exercises, catching energy via hacking the local landscape, and engaging with the material actors and histories of the power grid, are exercises of fostering energy literacy. By exposing what usually remains either unnoticed or unseen unless it breaks, bursts, fails, or becomes critical in times of crisis, our fieldwork was a lesson in acknowledging the greater material systems that shape the life we design for and affirm. How can this be expanded to work as an exercise that brings together considerations of material as well as immaterial relations of the power grid? Energy literacy when engaged at the intersection of design and the energy humanities needs to critically interrogate what the power grid is made of, who constructed it by which means and for which purposes, as well as the ways in which it warrants or denies access to resources and power, or shapes values, traditions, and realities. A complication of exercises suggests a further collaboration of these fields when it comes to questions like: What environmental design practices help us to develop literacy of the complex histories, ontologies, entanglements, and conditions of energy infrastructures? How could they encourage participation in discussions around privilege, power, justice, and consumption? Can we imagine anti-catastrophic energy futures that deal with the ways in which energy infrastructures have always been entangled with power relations?

Thank you to the workshop facilitators and participants, especially those who generously shared their sketches and photographs for this piece: Lucy Norris, James Auger, Mads Bering, Alexandre Nicolet, Ottonie von Roeder, Valentin Graillat, Jordi Tost, Rupert Neuhöfer, Ilkin Tasdelen. Thank you to the Matters of Activity Cluster who organized and funded the workshop. Images were altered to look like thermal paper prints.