Learning from Landscapes for the Post-Anthropocene

There is something captivating about destruction on an epic scale. The horror of it draws the eye and ear, pulling focus. Looking out across acres of scarred earth at the open cast lignite mine of Janschwalde near Cottbus / Chóśebuz in Lausitz (Lusatia in English) by the German-Polish border, the sheer magnitude of the anthropogenic change visited on the landscape is magnificent and catastrophic. Yet, scale and perspective are key here. Is it possible to look beyond this immensity and find that, at other scales and in other timeframes, there are stories evolving that transcend catastrophe?

This question was central to my project This Land is Not Mine, which began as an artistic research project supported by the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, Potsdam. Realised after two years work as a multimedia installation and music album, the research focused on identity in Lusatia, a region where Germany, Poland and the Czech Republic meet.This transnational region is the home of the Sorbian minority, and has been the site of wide-ranging lignite mining since the early twentieth century.

Now is the rubicon; a threshold that must be crossed into a post-extractive and post-anthropocentric time. I had been intrigued by how to prepare for this transition and how to find hope on the other side of ecological grief. So in 2020 I started artistic research in this enthralling landscape, just at the point when the German government announced that all mining activity would be stopped by 2038.

Identity is an important lens through which to engage with Lusatia and to look beyond catastrophe. The open cast lignite mining, which involves scraping away the earth’s surface by driving a digger the size of a house, has given economic security with one hand while taking away homes and historic sites with the other. Hundreds of villages, mostly Sorbian, were destroyed in the process, adding to existing challenges for maintaining Sorbian culture and heritage. Needless to say, the relationship of the region with extraction of long carbon reserves (or, as they are more commonly known, fossil fuels) is extremely complex and many entities hold a stake in the consequences and future of the activity, including humans, waterways, plants and animals.

The dominance of the large opencast mines on the landscape is paralleled in their dominance in the external narrative of Lusatia's identity. However, with the industry set to end in just under 20 years and old mines already filled with water across the region, questions remain: what will fill the holes left by the mines in the region’s future economy and industry, and in people's hearts?

The project encompasses more than the human elements of the region’s identity, however. As with much of my work, This Land is Not Mine addresses the more-than-human entities within an ecosystem, such as the water, the air, insects. My first approach to the project was through the landscape and the entities comprising it alongside the human.

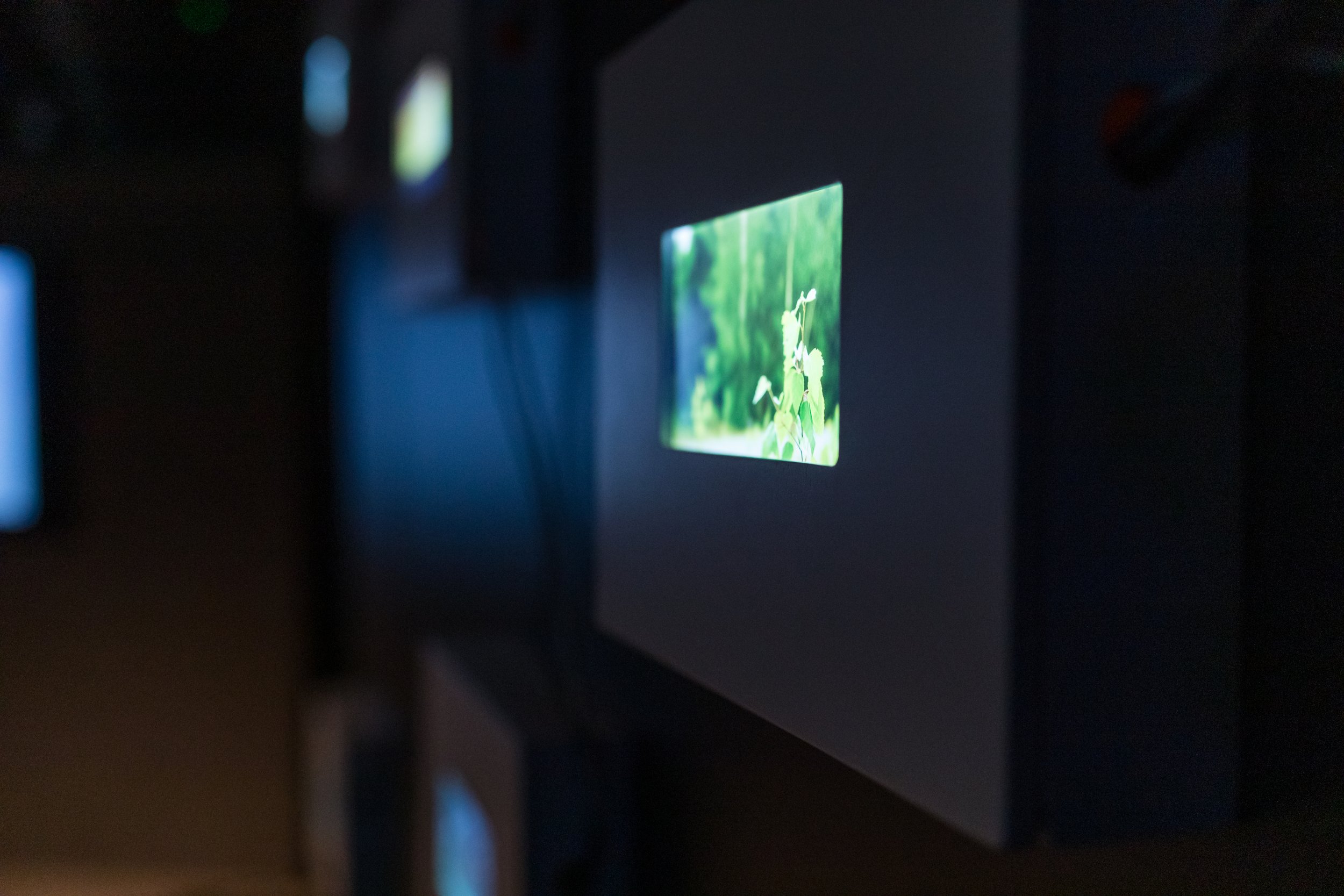

Stills from This Land is Not Mine videos credit Kat Austen CC-BY-SA 4.0

Rolling back to the early summer of 2020: I found myself on a sandy path near the sun-baked lake at Großräschen in Southern Brandenburg, the fluttering, translucent leaves of the birch trees around me casting dancing shadows on the sandy coppice floor.

Water is important in Lusatia. It is a central theme to some of the region’s Fairy Stories, which refer to bodies of water such as healing springs and the origins of rivers. The Spreewald, the forest around the River Spree, which springs forth from the Lusatian hills, is a famous tourist site frequented by hikers and bird watchers. But now, droughts get worse every year. The groundwater levels have been artificially lowered by constant pumping, so that mining activities can go deep enough to extract two layers of brown coal. Sometimes the river’s water runs rusty red as a consequence of the mining. This coal is burned in power stations located near to the open cast mines, which generate electricity, carbon dioxide and other pollutants. Lignite – brown coal – is one of the least efficient and dirtiest forms of carbon used to generate energy, and of course these emissions contribute to the climate emergency. In Lusatia, the climate crisis is felt through water; the rain has been coming less often, and when it does come, it rains hard.

I had been cycling in the summer heat around the lake at Großräschen, exploring the legacy of open cast mining. Ten years earlier, after the closing of the mine there, the giant pit left in the landscape had been flooded to create a recreational area. The water at Großräschen is hard to reach; the banks are unstable and until recently the water was too acidic for bathing. I had spent the day lying on forest floors to record video and audio of birch trees. The only way I could take a sample of water from the lake was by dangling a jam jar over the side of the empty marina using a length of the string I always carry with me on field recording adventures. Upon pulling it back up, I was sure I could feel the skin on my hands tingling where the water had touched it.

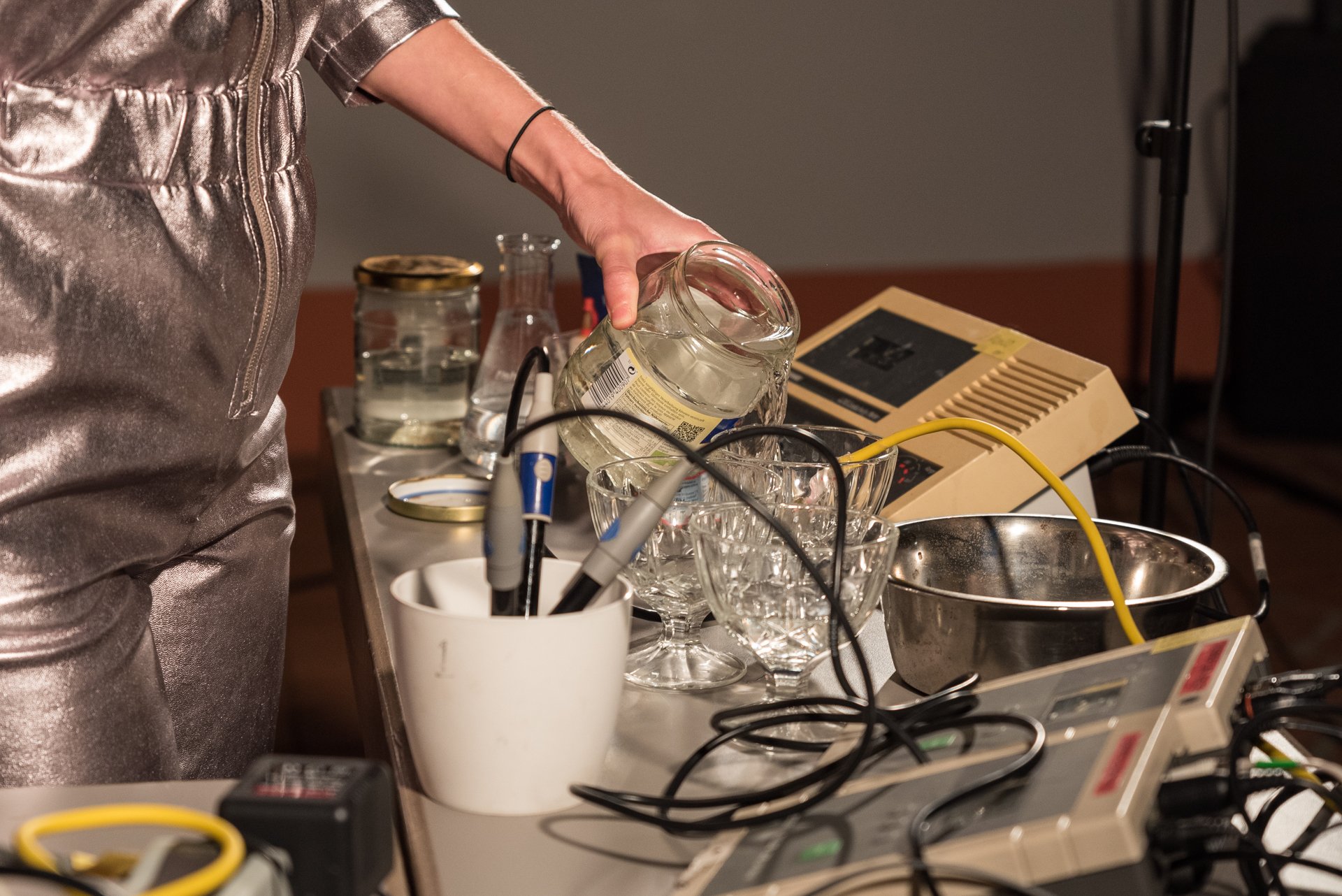

Through my landscape-based research, on trips like this, I touched the water, used hydrophones to listen under the surface. I also use more technological means to explore chemical characteristics of the water that are otherwise hard to sense. A few years earlier, I had the chance to develop a series of sound instruments by adapting scientific lab equipment that measures how acidic and how clean the water is. My hacked instruments now make sound from the process of measuring the chemical signature of water from different places (you can read more about that here).

Taking samples of the water and translating them into sound, I wanted to find out what was characteristic of Lusatia, what elements of identity existed in the region with and beyond mining. I read folktales, news reports, scientific papers. Simultaneously, I began to reach out to people living in the region in an effort to understand identity in this transitioning landscape and together to gather sounds that represent Lusatia.

I set up a crowdsourcing platform to create a database of sounds that Lusatian residents identify with the region. In response to coronavirus restrictions on participatory events, the microsite also shares listening exercises and sound recording techniques. The method of field recording is introduced as a medium for opening up the body to its surroundings and interrogating affective engagements with elements of the landscape that shape the region's as well as listener's identity.

During one of the rare suspensions of restrictions during the first year of the pandemic, I ran a workshop for This Land is Not Mine at the Brandenburg Museum of Modern Art in Cottbus in Lusatia where we explored the soundscape of urban waterways in the context of the project. I also helped plant a forest farm in rural Brandenburg, and joined discussion groups and workshops about identity in the region. I also collaborated with a local artist, Inna Perkas, to stage a responsive happening outside the iconic Brandenburg Technical University Library in Cottbus.

Photos from This Land is Not Mine performances (credit Andreas Baudisch) and installation (credit Miha Godec)

Through prolonged visits to different parts of Lusatia, I collected a plethora of video and audio recordings that began to take shape as vignettes of the multiple components of the identity of this transitioning region.

// Realisation of an aesthetic

The realisation of This Land is Not Mine as an artwork was iterative and occurred in conversation with the research. What emerged was an aesthetic spanning scales and timeframes, an aesthetic beyond catastrophe. The final forms are an installation combining 20 channel video with a 2 channel soundscape, a 7-track album of experimental music, and the crowd-sourcing website along with its database of sounds.

Drawing from chemical and climate science approaches to dynamic systems, I developed a framework for working with video material based on different classes of chemical reaction to derive three lenses by which to understand what I had encountered. The steady state refers to a reaction at equilibrium, where things are dynamic yet balanced. Dissipative states are constantly losing material and energy to the environment in which they occur. And multi-state systems have multiple states in which equilibrium is reached. The installation of 20 separate channels is presented as a 7-6-7 triptych across these three perspectives, spanning a total of 16 metres. Each of the synchronised video channels is presented on 7-inch screens housed in bespoke wooden frames and accompanied by a soundscape composed using field recordings from Lusatia.

In working with these video and audio recordings, the challenge was to engage fairly with the landscape. The aesthetic of mining, both in terms of sounds and visuals, is of such epic proportions that there is a risk to be engulfed by it. At other scales and across time there is a great deal of beauty and variety that tells a richer story, accessible through close attention, through embodied and technological mediation.

Inspired by the multiple coexisting stories and identities encountered in Lusatia, the structure of the album This Land is Not Mine draws on structures prevalent in folk and protest albums. Each song takes the perspective of a different protagonist, such as the River Spree, the city of Cottbus or the fabled healing fountain of Duborka. Many of the melodies are inspired by folk songs, both the Sorbian songs I encountered during my research and the Celtic songs that I grew up singing. The album, released digitally, is presented as a complete, concept album performance during which I use my specially adapted labware to play samples of water from Lusatia alongside samples of water local to the performance location.

Both outputs elaborate on the complexity of identity. They highlight the importance and diversity of subjectivity (human, non-human and more-than-human) in relating to place, and the importance of scale in exploring post-extractive and post-anthropocentric aesthetics. That mutual understanding is key to finding routes forward. In recognizing and working with these aesthetics from landscapes that are so wickedly entangled with industrial extraction and consumption, the release of carbon dioxide and other pollutants, one has the tools to imagine a future beyond the catastrophes that fade in and out like spectres of our future.

Indeed, I propose that engaging with post-extractive landscapes is a vital aspect of reframing the dialogue against catastrophe, and of being empowered by it. As humans stand on the brink of the post-anthropocene, we must adopt new – or old – ways to be, ways to relate to the world and other(s) within it. Whether contemporary experimentation with these modes happens in post-extractive, urban, rural or post-industrial landscapes, collectively humanity faces an extraordinary opportunity to reshape itself within the world it has created.

More information on This Land is Not Mine

This Land is Not Mine was most recently presented as part of the Carbon Echoes Trilogy and performed live at Ars Electronica Festival 2022 7-13th September 2022. ///

This text is adapted from the forthcoming catalogue Fossil Experience by Kat Austen (2022) ISBN: 9783000725371

This Land is Not Mine performance at Serbpop 2.0 –

Full Serbpop 2.0 programme on the RBB Serbski Program

This Land is Not Mine Minutae of Home track – can be downloaded from here for free